Acknowledgements

Chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy in cancer patients compose a future risk of developing a therapy related myeloid neoplasm (TRMN). However, the presence of a germline landscape might contribute and modify the overall risk. It has been suggested that around 18.5% of TRMN patients have a germline cancer mutation. In particular, cancer predisposing genes or syndromes involving alterations in the DNA repair mechanism such as CHEK2, BRCA1, BRCA2, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 or PMS2 might be enriched in patients who develop a primary tumor (PT) and a subsequent secondary myeloid neoplasm. The role of the alterations in cancer susceptibility genes in association with the treatment for the PT in the development of TRMN is still unclear.

To evaluate the clinical and genetic landscape of TRMN patients to understand the role of different risk factors and provide tools for differential diagnosis and clinical management.

Clinical evaluation of 96 patients with TRMN and 12 patients with a secondary myeloid neoplasm after a non-treated with chemotherapy primary tumor (nTMN) was performed. In addition, germline landscape and somatic alterations were studied in the TRMN series by tNGS (N=49) and WES (N=47). Tumoral sample was obtained from bone marrow. CD3+ T lymphocytes from peripheral blood (PB) were enriched by immunomagnetic selection and used as germline/control sample. A minimum of 98% purity in CD3+ was selected to prevent myeloid contamination. Variant frequency (VAF) <30% found in tumor but not in CD3+ sample was annotated as somatic alteration. Only pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants were considered.

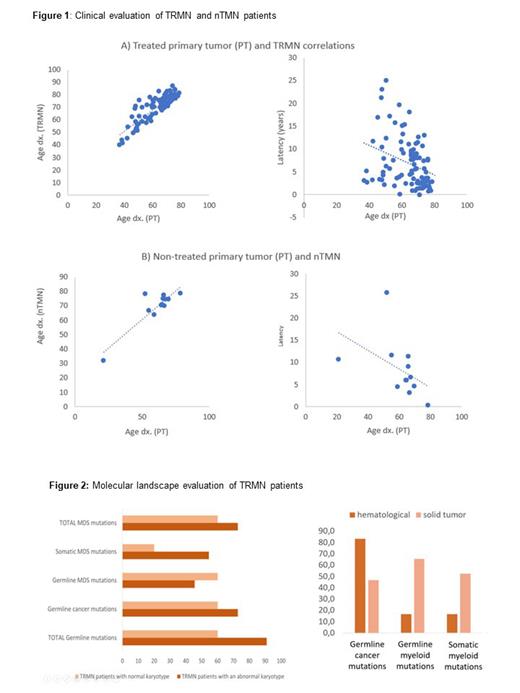

The median age of onset was 62.3 and 71.1 years for the PT and the TRMN, respectively. 32.5% had complex karyotype. Similar positive correlation was found between the age of onset of the PT and the age of onset of the TRMN and nTNM. A negative correlation was found between the age of onset of the PT and the latency until the TRMN and nTMN diagnosis, which suggests that elderly age condition is more relevant than the cytotoxic treatment (Fig.1). No differences in latencies were found between MN subtypes, despite ring sideroblasts and del(5q) myeloid subtypes correlated with shorter and higher latencies, respectively. Different latencies were neither found when the PT was solid or hematologic, but interestingly, TRMN patients with previous colorectal cancer had shorter latencies.

On the other hand, 91.3% of the TRMN patients presented a molecular alteration (considering both genetic or cytogenetic alterations), including 60.9% and 75% of patients with germline and acquired alterations, respectively. Germline mutations included 52.2% and 47.8% annotated in cancer predisposition genes of the DNA repair mechanisms and myeloid genes, respectively. Only 39.1% of TRMN patients were found with pathogenic somatic variants in myeloid genes while 68.75% were found with an abnormal karyotype.

Finally, higher number of germline and somatic mutations was found in TRMN patients with an abnormal karyotype. However, a higher percentage of germline mutations in myeloid genes was found in TRMN with a normal karyotype (Fig.2). Higher percentage of molecular alterations (both germline and somatic) in myeloid genes was found in TRMN patients with a previous solid PT. However, higher percentage of mutations in cancer predisposition genes was found when the PT was hematologic.

Our results highlight the role of mutations in cancer predisposition genes in the development of TRMN.

Similar latency associations were found for TRMN and nTMN patients, which suggest that other risk factors different than treatment might contribute to the TRMN development.

Altered karyotypes in TRMN patients are associated with acquired mutations in myeloid genes but not with germline mutations, which suggests two different entities with different prognosis.

Molecular alterations in myeloid genes are more relevant in TRMN patients with solid PT, while molecular alterations in cancer predisposition genes are associated with TRMN patients with hematologic PT.

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministerio de Economia y Competitividad, Spain (PI 20/00531)(Co-funded by European Regional Development Fund. ERDF, a way to build Europe). 2021 SGR 00560 (GRC) Generalitat de Catalunya; economical support from CERCA Programme and Fundació Adey.

Disclosures

Montalban-Bravo:Rigel: Research Funding; Takeda: Research Funding. DiNardo:Servier: Honoraria; Notable Labs: Honoraria; Fogham: Honoraria; Novartis: Honoraria; AbbVie/Genentech: Honoraria; Astellas: Honoraria; BMS: Honoraria; ImmuniOnc: Honoraria; Schrödinger: Consultancy; Takeda: Honoraria. Jerez:Astrazeneca: Research Funding; Novartis: Consultancy; GILEAD: Research Funding; BMS: Consultancy. Diez-Campelo:Gilead Sciences: Other: Travel expense reimbursement; BMS/Celgene: Consultancy, Honoraria, Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees, Other: Advisory board fees; Novartis: Consultancy, Honoraria, Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees; GSK: Consultancy, Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees. Garcia-Manero:Genentech: Research Funding; Bristol Myers Squibb: Other: Medical writing support, Research Funding; AbbVie: Research Funding.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal